Why I want to take down capitalism and build new systems:

I believe capitalism to be an economic system that, by its very nature, creates economic divides resulting in harm, violence and injustice for both people and the planet. I also see and experience capitalism as a system of domination that disproportionately extracts and exploits resources from people and the planet. Any shift away from our current economic system must be rooted in a framework of collective empowerment, liberation, healing and health for both people and the planet. I bring these beliefs and experiences into my organizing against capitalism, against exploitative and extractive systems, against violence, harm and dehumanization. I work in solidarity with those collectively and collaboratively creating healthier economies and a healthier planet.

Yes, I want to bring capitalism down and dismantle current systems of oppression. I also want to build and create what I want to see in the world, something that we can move towards. We cannot run away from capitalism in an unorganized frenzy. For if we do, those most vulnerable will be left behind, trampled and exploited, yet again. We must be diligent and proactive in building bridges that lead to what we want to see in the world, making sure to support our most vulnerable and most oppressed selves to get there and lead the way. We must have an escape plan.

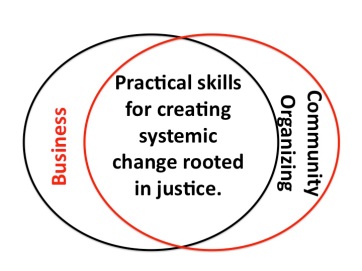

Three distinct sectors speak to me as a place of hope for alternative economies, for healthy communities, selves and ecosystems. I see worker-coops and community-supported businesses as answering the “what” question of creating alternative structures; they counter the current exploitation model of businesses by creating democratic ownership and management structures as well as a direct tie to community needs and values. However, it is also important to acknowledge that oppressive systems can be carried into these structures. Thus, including social justice organizations answers the question of “how” we will be building alternative economies

Focus on worker-coops, community-supported businesses and social justice organizations:

Cooperatives can take many shapes and forms, from agriculture coops to member coops, producer coops to worker coops. While all coops have some sort of paradigm shift inherent in their structure, I want to focus on supporting worker-coops specifically. Worker-coops are game-changers because of their democratic governance and direct ownership of the business. Worker-coops defy capitalism because of the removal of a boss and a subsequent empowerment of worker-owners. The very structure of worker-coops mandates a paradigm shift from top-down authority to horizontal collaboration. Because all workers are owners, profits are actually seen as surplus and are invested back into the business and/or divided amongst worker-owners as decided democratically by the worker-owners. There are many unique challenges facing worker-coops based on both the lack of hierarchical structure and the investment abilities of each member-owner.

Community-supported businesses are financially supported by their communities: friends, family, geographically or culturally communities. Community-supported agriculture farms (CSAs) are the most familiar and popular forms of community-supported businesses. What draws me to community-supported businesses are their lack of dependency on traditional bank loans/investments; potential ability to buck the interest system; creative use of community resources and inherent ability to create value for their community. Community supported businesses use a membership-based model in which customers actually buy “shares” (of food, of meals, of yoga classes, of time in a print studio) of the business. This method is as a pre-buy revenue generator that acts as both a short-term loan for the business and as a sign of creating needed value in the community. Community-supported businesses are important to communities who either cannot capital from traditional methods.

Social Justice Organizations are the third entity that I feel are important to support in building alternative economies. Capitalism is inherently dependent on a divide-and-conquer mentality. Issues of racism, classism, transphobia, ableism, etc. are all used to support and maintain the current economic and power systems that exist. To support only businesses and organizations with alternative structures means that those structures would carry with them the same issues of oppression and violence inherent in capitalism today. It is important to me to support grassroots community organizing that is rooted in social justice principles in order to actualize and achieve collective liberation. This looks like supporting the leadership of historically marginalized communities, understanding the ways that historically marginalized communities have been systemically treated differently – often through violence, genocide and lack of access to resources – and creating systems that actively work against current systems of oppression and towards empowerment and equity. To support worker-coops without bringing in a racial or economic justice lens would mean leaving out people of color and poor people from being able to transition to healthier economies. If worker-coops and community-supported businesses are examples of what we are transitioning to, grassroots social justice organizations important to maintain a vision of how we are going to transition. And, because the leadership and membership of these organizations has often been marginalized and/or lacked access to resources and power, it is imperative to support their viability and stability.